By Mehdi Asgari, Senior Engineering Manager for IT, Security, and Reliability Engineering

If you drive a car that’s been produced in the past 5–6 years, chances are it’s equipped with many smart technologies and connectivity features; It could update its software wirelessly and automatically. It might have some advanced safety features like automatic parking, or it may be able to control and steer itself under certain conditions. It might let you control some of its features remotely via a mobile app. It may support app installation. The list goes on and on.

As the cars get smarter and more feature-packed, they also present new and complex challenges for manufacturers and regulators from a physical and cyber threat perspective.

I am Mehdi Asgari, Senior Engineering Manager for IT, Security, and Reliability Engineering at Vay. In this article, I will introduce the concept of cybersecurity in the automotive context, and show how it’s different from safety. You don’t need to be a safety or security expert to read the post, and I’ll avoid discussing complex technical topics.

Safety and (cyber)security are two different domains, yet many people confuse the two. The fact that many languages have one word for both concepts can contribute to the confusion. In German, both are called “Sicherheit”. In Russian, they are called “безопасность”. Yet there are languages like English and Persian which have unique words for each. Another contributing factor is how different industries used to look at these concepts: many engineers working in tech and IT are not exposed to the concept of safety, as for example there’s no physical harm possible to the users of an online retail shop or a classic SaaS. And on the other hand, safety is a concept more known to people working in certain industries (like automotive) that have the potential to cause harm or injuries, while traditionally cybersecurity was not considered in these industries at all! In fact, the first edition of the ISO 26262 standard (Road Vehicles – Functional Safety) was released in 2011, while the first version of ISO 21434 (Road vehicles – Cybersecurity engineering) was published a decade later, in 2021.

So depending on which sector you work in, you may have heard of one or both, but there’s still a confusion lingering in the air as to how exactly these two concepts are different.

Note 1: although my focus in this post is on the automotive industry, you should keep in mind that there are many other industries that either have safety standards, or consider safety very seriously in various stages of product design, development, and operations (Aerospace, railway, industrial automation, medical devices and the energy sector are just a few)

Note 2: the main audience of this document are people who are not experts at security, so I have oversimplified the concepts.

Let’s first have a look at the definitions:

- Safety in automotive systems is focused on preventing physical harm or injury to drivers, passengers, and pedestrians, via detecting and preventing collisions or reducing the severity of an impact. Examples of modern safety features include automated braking, lane-keep assistance, blind-spot detection, and adaptive cruise control.

- (Cyber)Security was not a big deal in the automotive industry in the past. Actually, the word “security” in the automotive context could have had different meanings (e.g. securing against unauthorized physical access to a car, theft-protection, etc.). Cars were not exposed to the outside world like they are today. But things have changed now, and it’s more probable for a car to get “hacked”. That could mean many things: from stealing a car via exploiting vulnerabilities in how the key fob communicates to the car, to stealing private user data stored on the vehicle. So security now is also focused on preventing these attacks.

Safety and cybersecurity are both critical considerations at Vay. Both involve protecting against potential hazards/threats that could cause harm to drivers, passengers, and pedestrians, but they differ in the nature of the threat and the measures used to address it.

As it’s obvious in the above definitions, safety usually deals with hazards (like collisions) and malfunctioning components. Most of the time, these are not directly caused by malicious people. On the other hand, security is more concerned with risks caused by malicious activities. Traditional physical security would focus on protections against breach and theft. Cybersecurity focuses on protecting against data theft, remote vehicle take-over, attacks against car sensors, attacks against communication network, etc.

One of the many principles used at Vay is “Security by Design”. This means building in cybersecurity measures from the beginning, rather than adding them as an afterthought.

We also need to understand the threats we’re exposed to, and the risks caused by them, to be able to protect against them.

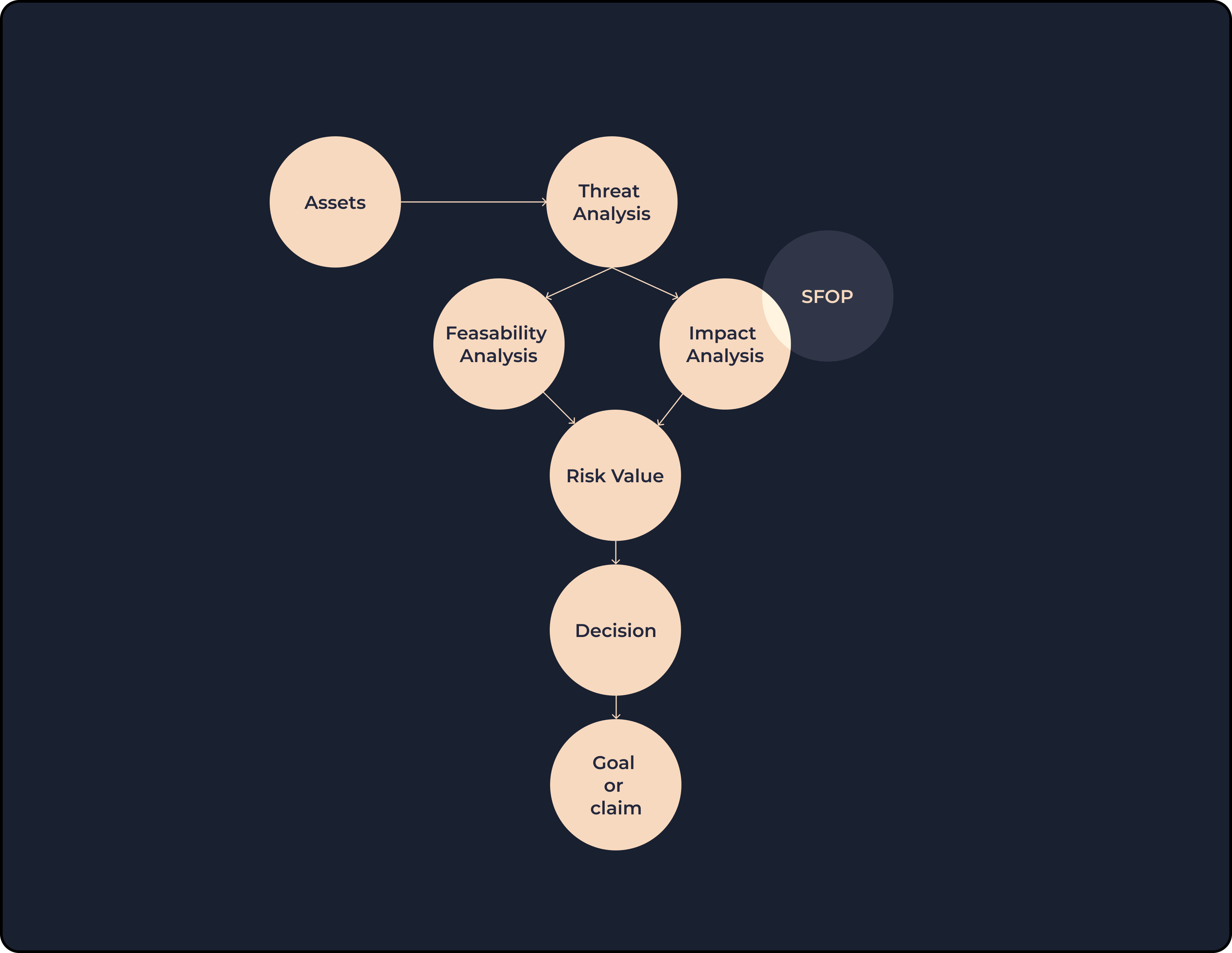

People working in the FuSa (short for Functional Safety) and Cybersecurity perform risk assessments on new product features to make sure they have a good understanding and assessment of known issues/threats and are also prepared to tackle unknown threats and faults. They call this process differently, though: HARA and TARA, respectively. TARA stands for Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment. This process begins with identifying the assets. Asset could be any component or system used in the product. It could be a virtual thing (like a piece of code) or a physical component, like a sensor or computing hardware.

In this process, we look at the scenarios that could pose a risk to each asset, and then we calculate the risk for each scenario. There are different methodologies and models that could be used for this purpose, and companies are free to choose their own. A risk could be low, medium, high or critical. Again, this is not a must. You’re free to adjust these for your own use cases, but we’ll stick to these for the sake of simplicity.

Now, the conscious reader may ask how can we classify a specific risk as low or high. Who could argue that? To calculate a risk value, we usually look at 2 parameters:

- Feasibility: how likely is it for this threat scenario to actually happen.

- Impact: what would be the severity of this specific attack.

Both these factors are again decided based on other parameters. And here’s where safety comes into play again: one way to measure the overall impact value is to look at the impact on 4 parameters: Safety, Financial, Operational and Privacy (SFOP for short). So a cybersecurity attack might have a safety impact.

Now, let’s get back to where we left off: after we have a final risk value, we need to do something about it. There are 4 common decisions that could be made about a risk:

- Mitigation: this is the most common approach, which is to use countermeasures against the threat we’re analyzing.

- Accept: simply accept the risk and do nothing.

- Delegate: transfer the responsibility to another entity (e.g. by using insurance)

- Avoid: do something to avoid the risk altogether.

The first two are more common. When we mitigate a risk, we then define a security goal; The list of security goals is an output of TARA. A security goal is very high level. For example, you might have a goal to make sure the integrity of the code and data stored on your ECU is ensured. Now you need to break it down to multiple security requirements that are more understandable and concrete for the various engineering teams to understand and implement.

In case you accept a risk, you don’t need to define a security goal for it. Instead, you define a security claim (you’re claiming that this specific risk can be tolerated and accepted). The list of claims could be another output of the TARA.

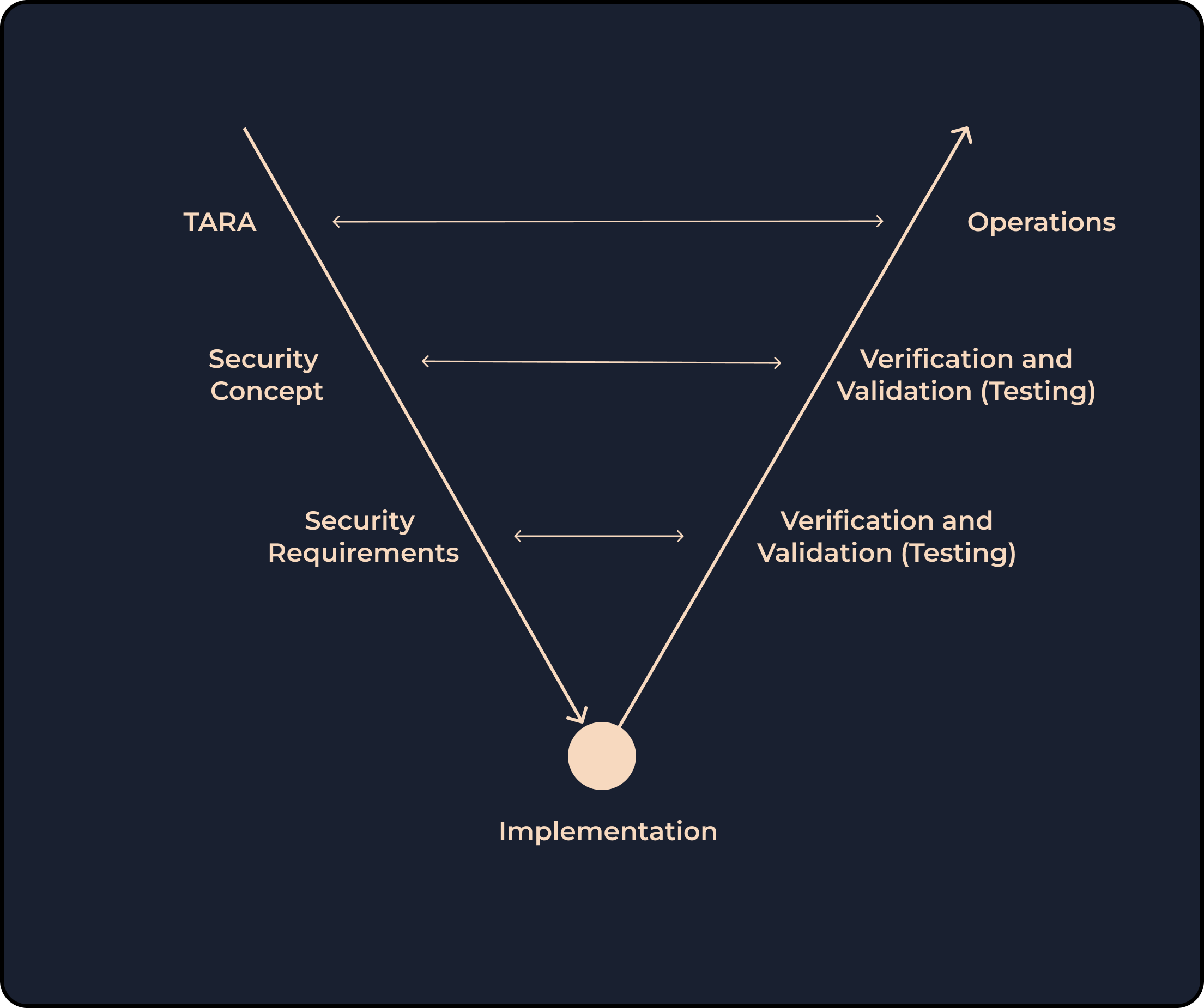

You might be familiar with the V Model used in software development lifecycle or in functional safety; There’s a similar concept used in cybersecurity. Look at the simplified picture below; the left leg of the V starts with risk assessment, and goes into detail (defining a high-level concept, defining technical security requirements) and then the right leg verifies and validates (tests) the requirements and goals defined in the left leg.

So far, I focused on the left leg, which is analyzing the threats and assessing the risks, and coming up with requirements. Another equally important part of the security is the whole security tests (validation tests, penetration tests, etc.) which are represented in the right leg of the V shape above. Here, we validate the requirements that we’ve defined, by testing them to make sure they’re properly implemented.

There are many different sorts of manual and automated security tests, done in various different intervals, or based on some external triggers. Examples of security tests done in Vay:

- Requirements validation

- Release tests (this could have many tests in common with #1)

- Security scanners (testing the code to find security flaws)

- Security penetration tests

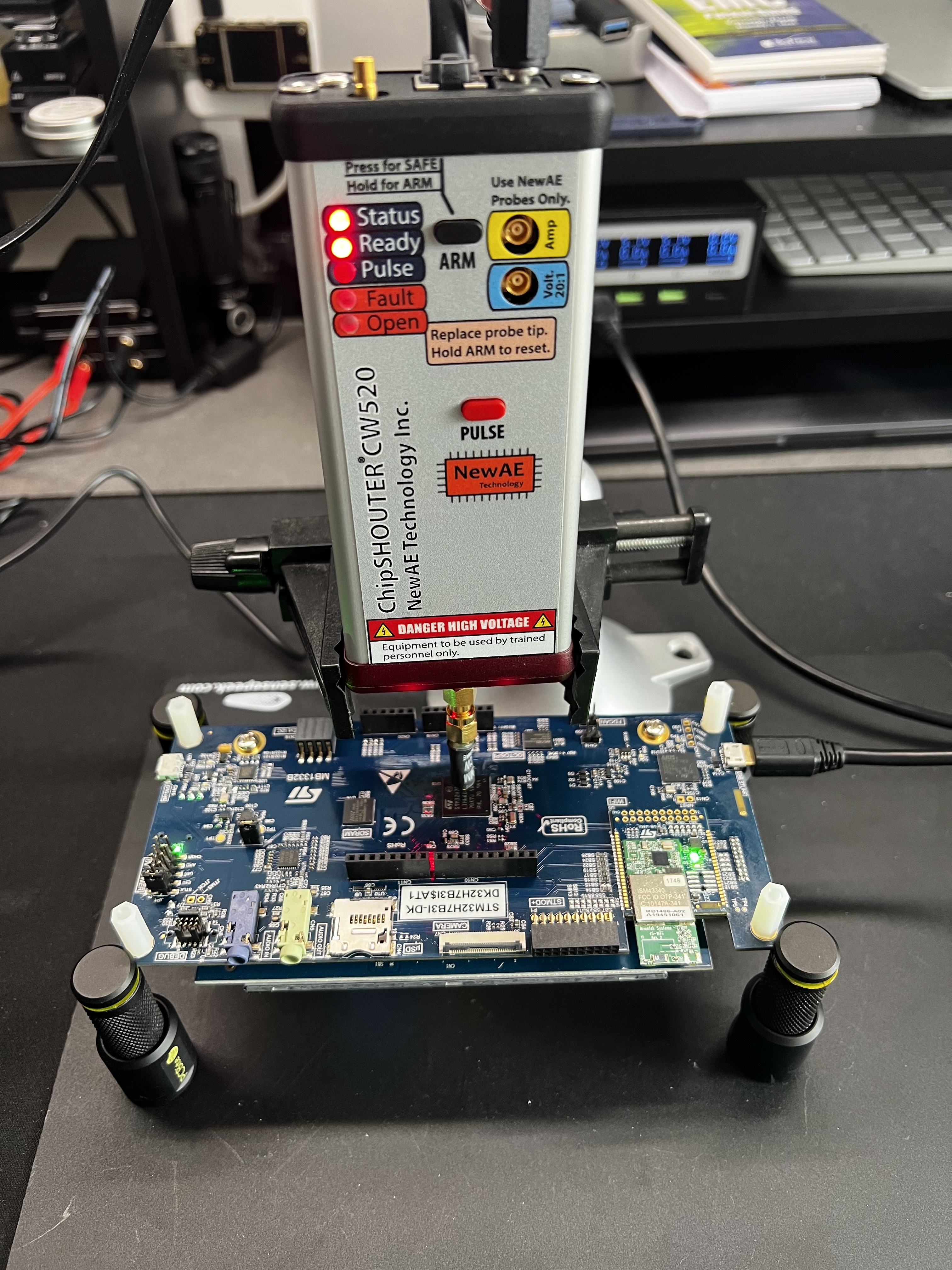

- Hardware security tests, to find issues in the hardware we use

- Attack simulations: to simulate an exact attack on our product or infrastructure, as defined in our TARA.

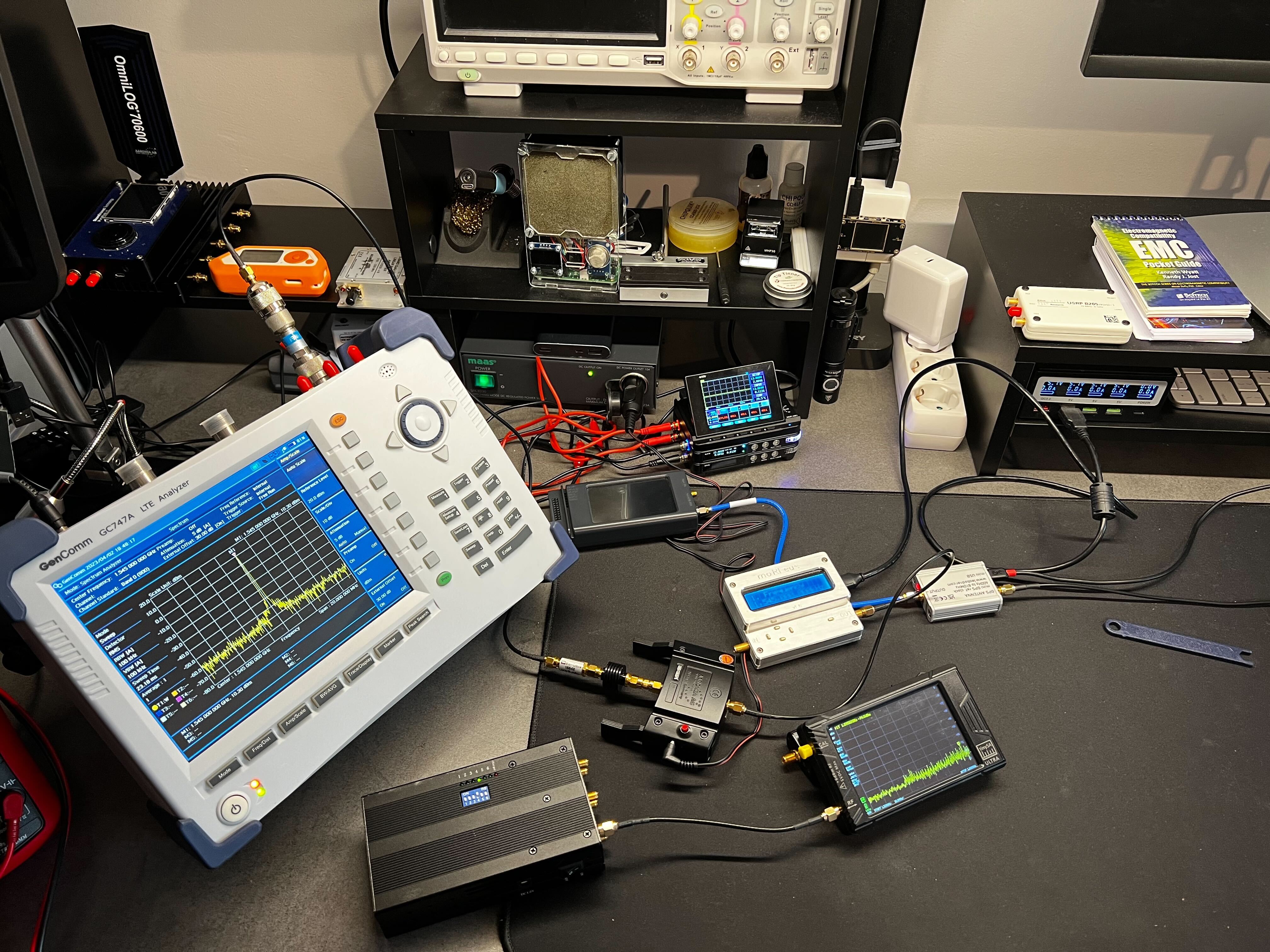

Here are 2 photos of hardware and wireless security tests.

I hope you’ve learned something about the difference between safety and cybersecurity.

I will dive deeper into some of these topics, like advanced security tests, in a follow-up article.

Here are additional resources to read about these topics:

- ENISA’s “Good Practices for Security of Smart Cars”

https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/smart-cars - ISO 21434 standard text (you have to purchase it)

https://www.iso.org/standard/70918.html - ASRG’s YouTube channel

https://www.youtube.com/@automotivesecurityresearch1613/videos

Book: Building Secure Cars

https://www.amazon.de/-/en/Dennis-Kengo-Oka/dp/111971074X/